God’s Punishment and Racial Prejudices: A Historical Perspective

The notion of divine punishment has been used throughout history to justify numerous social injustices, including racial prejudices. This concept appears clearly in “One-Legged Uncle Jesse,” where religious beliefs are wielded to explain and validate racial discrimination.

A father’s conversations with his daughter Arvis offer an emotional look into how such ideas are passed down from one generation to another, perpetuating systemic racism.

In one particularly unsettling conversation, Papa tells Arvis, “God punishes some people by making them black.” When Arvis inquires with a question, “What did they do?”, Papa responds, “I don’t know why God punished them.

They did something to make him angry, probably something evil, and he made them black so they would suffer and learn their lesson.”

The Historical Use of Religious Justifications

Throughout history, interpretations of religious texts have often been molded to justify racial oppression.

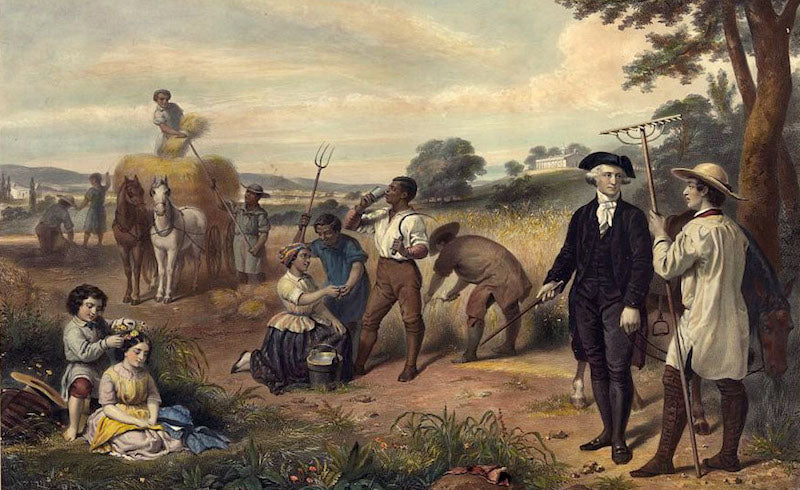

During the era of American slavery, many slaveholders pointed to the Bible as a means to validate the enslavement of African Americans. Passages were selectively interpreted to assert that people of African descent were inherently inferior and destined for servitude as a divine punishment.

This religious justification didn’t end with slavery; it continued into the era of segregation and Jim Crow laws. Whites preached the notion that blacks were cursed and thus should remain subservient. Papa’s explanation to Arvis is a direct reflection of this historical misuse of religious doctrine.

The Impact on African American Communities

The belief that black people were cursed amplified their persecution and allowed for a dehumanization that justified heinous acts. This is echoed in the book through the character Haskell, whose father forced him to participate in a Klan lynching.

The victim was the uncle of one of Haskell’s Colored friends. This gruesome act was not an isolated incident but part of a long history of racial terror used to enforce white supremacy.

This concept of divine punishment thus became a way to mitigate guilt and justify the continuation of racism. It shifted blame away from the perpetrators of racial injustice and onto the victims themselves.

Real-World Events Reflecting These Themes

One historical example illustrating the use of divine punishment to justify racial prejudice is the case of the Scottsboro Boys in the 1930s. Nine African American teenagers were falsely accused of raping two white women in Alabama.

Despite clear evidence of their innocence, they were convicted by all-white juries. The surrounding cultural belief in the inherent guilt and divine punishment of black people played a crucial role in their unjust treatment.

Additionally, the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 60s faced significant religiously-motivated resistance. Opponents of desegregation frequently invoked religious arguments to maintain the status quo. They claimed that racial hierarchy was divinely ordained, much like Papa’s distorted teaching to Arvis.

The Psychological Toll

The internalization of these beliefs has a deep and lasting impact, as seen with Arvis’s reaction. She feels a sense of fear, a “twinge of fear that God might turn her black,” which brings to light how such teachings can instill a form of spiritual and psychological terror in young minds.

This fear is matched with a sliver of empathy for her Ma’s disregard for the White Man’s religion, indicating the beginning of her internal conflict about these beliefs.

Haskell’s storyline adds another layer to this discussion. When Haskell’s father forces him to participate in a lynching, it becomes a traumatic event that fundamentally changes him.

His forced participation in the act of racial violence instills in him a deep sense of rage and irreparable loss. The compounded layers of racial prejudice and divine justification lead Haskell to the violent act of hitting his father and ultimately leaving him to die, which symbolically ends the cycle of violence perpetuated by his father.

Turning to Future Generations for Change

To break this cycle of divine justification for racial prejudice, it is crucial to challenge and reinterpret these long-held beliefs. Open dialogues, like the shaky yet crucial conversations between Papa and Arvis, are necessary steps toward deconstructing these harmful ideas.

Educational initiatives and cultural shifts are fundamental. Society must aim to teach children like Arvis the values of equality, empathy, and justice from a balanced and humane perspective. By doing so, we can hope to end the justification of racial prejudice under the guise of divine punishment.

Final Words

The dialogue in “One-Legged Uncle Jesse” captures the deeply ingrained and destructive belief that racial inequalities are divinely sanctioned. Through historical context and poignant character narratives, it showcases the harmful consequences of these beliefs.

The cycle of hatred and violence, portrayed through characters like Haskell and events like the Scottsboro Boys trial, underlines the urgent need to rethink and challenge the use of religious justifications for racial prejudice.

By addressing and correcting these flawed ideologies, future generations can hope to build a more just and empathetic society.